(cuộn xuống dưới để đọc tiếng Việt)

Hello you, you who have wandered into my blog. Thanks for being here. My most current works now live at https://medium.com/@linhngo. If you have a Medium account (which can be set up super easily with your Facebook or email), feel free to follow me there.

English posts are in Sciwalk Cafe.

Vietnamese posts are in Tập Tầm Vông.

While you are here, feel free to browse through my previous writing. Enjoy your stay, and I hope to see you over there in Medium.

Linh

---------------------------------------------------------

Bạn gì vừa vào blog của mình ơi: Cảm ơn bạn đã lạc đến đây. Dạo này mình chuyển sang viết bài bên https://medium.com/@linhngo bạn nhé. Nếu bạn có tài khoản Medium (nối từ Facebook hoặc email sang rất là dễ) thì theo dõi mình trên đó nhé.

Bài tiếng Anh: Sciwalk Cafe

Bài tiếng Việt: Tập Tầm Vông

Trong lúc còn vương vấn ở đây, xin cứ tự nhiên thăm quan các bài cũ của mình. Hẹn gặp lại bạn bên Medium nhé.

Tập Tầm Vông

Thứ Năm, 10 tháng 3, 2016

Thứ Sáu, 4 tháng 3, 2016

Câu chuyện Marfan của tôi, Phần 3: Gien dở hơi

My Marfan tale, Part 3: Odd gene.

Xin đừng nhìn thấy tiếng Anh mà sợ. Như mọi khi, dưới mỗi đoạn đều có dịch tiếng Việt. Ba tôi không hiểu sao cho rằng tôi chỉ viết bằng tiếng Anh, thế nên lần này tôi cho tiêu đề tiếng Việt lên đầu xem sao.

Phần 1: http://taptamvong.blogspot.com/2016/02/my-marfan-tale-part-1-dislocated-lenses.html

Phần 2: http://taptamvong.blogspot.com/2016/02/my-marfan-tale-part-2-broken-heart.html

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~``

I teach General Genetics every year. My students are young and bright sophomores determined to become doctors. After the first three weeks, I would camouflage my story in a question and let them play doctor.

Hàng năm tôi đều dạy Di truyền học Đại cương. Sinh viên của tôi hầu hết là các bạn năm hai, rất trẻ, rất sáng dạ, rất muốn trở thành bác sỹ. Sau khoảng 3 tuần, tôi sẽ ngụy trang chuyện của tôi thành một bài tập để cho các bạn sinh viên chơi trò bác sỹ.

Xin đừng nhìn thấy tiếng Anh mà sợ. Như mọi khi, dưới mỗi đoạn đều có dịch tiếng Việt. Ba tôi không hiểu sao cho rằng tôi chỉ viết bằng tiếng Anh, thế nên lần này tôi cho tiêu đề tiếng Việt lên đầu xem sao.

Phần 1: http://taptamvong.blogspot.com/2016/02/my-marfan-tale-part-1-dislocated-lenses.html

Phần 2: http://taptamvong.blogspot.com/2016/02/my-marfan-tale-part-2-broken-heart.html

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~``

I teach General Genetics every year. My students are young and bright sophomores determined to become doctors. After the first three weeks, I would camouflage my story in a question and let them play doctor.

Hàng năm tôi đều dạy Di truyền học Đại cương. Sinh viên của tôi hầu hết là các bạn năm hai, rất trẻ, rất sáng dạ, rất muốn trở thành bác sỹ. Sau khoảng 3 tuần, tôi sẽ ngụy trang chuyện của tôi thành một bài tập để cho các bạn sinh viên chơi trò bác sỹ.

"Emily is an eight year old girl who has recently been diagnosed with Marfan syndrome. Marfan syndrome is a dominant genetic disorder caused by mutations in genes that code for connective tissue proteins such as fibrillin or collagen. The typical signs of this syndrome are tall and lanky build, dislocated lenses, flexible joints, and lungs problems. Emily has all of these signs.

In patients with Marfan, the aorta may become enlarged and ruptured, which is extremely dangerous and potentially fatal (40% of Marfan patients will die immediately if aorta dissection occurs, the risk of death is between 1% to 3% per hour after the dissection event). Patients should avoid demanding physical activities and contact sports to avoid putting extra strain on the aorta and the heart. Aorta abnormality can be detected early by regular echocardiograms. A drug called Losartan can slow down aorta growth rate. If necessary, surgeries can be indicated prior to aorta dissection event and can decrease the risk of death to less than 2%.

Your medical team consisting of a family physician, a genetic counselor, and a specialist of your choice. Your team is in charge of Emily's and her family's care. Draft a monitoring and treatment plan and explain it."

"Emily là một cô bé tám tuổi, gần đây vừa được chẩn đoán mắc hội chứng Marfan. Hội chứng Marfan là một tật di truyền trội, do đột biến gien mã hóa protein mô liên kết (như fibrillin hay collagen) gây ra. Các dấu hiệu thường gặp của hội chứng này là tạng người cao gầy, lệch thủy tinh thể, khớp biến dạng hoặc linh động, dễ mắc bệnh phổi. Emily có tất cả các dấu hiệu trên.

Bệnh nhân Marfan có nguy cơ giãn và bóc tách động mạch. Đây là một biến chứng rất nguy hiểm và có thể gây tử vong (40% bệnh nhân Marfan tử vong ngay lập tức khi bị bóc tách động mạch, nguy cơ tử vong tăng 1% đến 3% mỗi giờ sau khi động mạch bắt đầu bóc tách). Bệnh nhân phải tránh hoạt động mạnh và các môn thể thao cường độ cao để tránh gây thêm áp lực lên tim mạch. Siêu âm tim thường xuyên cho phép phát hiện các dấu hiệu bất thường của động mạch từ rất sớm. Chỉ định thuốc Losartan có thể làm giảm mức độ giãn động mạch. Nếu cần thiết, có thể chỉ định phẫu thuật trước khi động mạch bóc tách, làm giảm nguy cơ tử vong xuống thấp hơn 2%.

Nhóm của bạn gồm có một bác sỹ đa khoa, một chuyên gia tư vấn di truyền, và một bác sỹ chuyên môn tùy bạn chọn. Nhóm này được giao chăm sóc sức khỏe cho Emily và gia đình cô bé. Hãy soạn một liệu trình giám sát và điều trị, đồng thời giải thích cho bệnh nhân và gia đình."

Then I watch them jump into discussion. You might as well imagine that you are watching a movie here. My students are the hero going into a mysterious landscape to fight a dragon, rescue everyone and save their lives. As movie audience, you gasp when the hero almost fall off a cliff and you yell when they tumble into obvious traps. "You miss the mother! The dragon got her! Save her! No, don't go, come back, save her!" Such an obvious trap, you sigh.

Rồi tôi ngồi xem các bạn ấy xông vào thảo luận. Bạn đọc có thể tưởng tượng như là chúng ta đang xem phim vậy. Sinh viên của tôi là siêu nhân xông vào một vùng đất bí hiểm để chiến đấu với quái vật và giải cứu con tin. Là người xem, bạn có khi sẽ hết hồn khi siêu nhân suýt nữa thì rơi xuống vực, và bạn có khi sẽ cáu ầm lên khi họ rơi vào những cạm bẫy rõ lù lù ra là bẫy. "Quên mất bà mẹ rồi kìa! Con quái vật bắt được bà mẹ rồi! Cứu bà mẹ đi! Quay lại đằng sau, cứu bà mẹ!" Bẫy rõ lù lù ra thế mà, bạn thở dài.

Let's be fair: my students haven't read my blog. They have no clue how the movie would turn out. They are in it. They are in a maze of genes and mutations and pedigrees. They see Marfan the Dragon coming for Emily, and they protect her with echo and orders to stay away from sports. They brandish their weapons of Losartan and surgeries. They worry about Emily's hypothetical children who would have 50% chance of getting Marfan. Emily's life is a straight line that starts here, now, with her diagnosis of Marfan, and it will only go into the future with possible complications and possible sick children. It is the future of Emily that they travel to and get stuck in.

Công bằng mà nói, sinh viên của tôi đã đọc blog này đâu. Họ đâu biết kết cục phim sẽ như thế nào. Họ đang ở trong phim kìa. Họ lạc trong một mê cung với gien rồi đột biến rồi bảng phả hệ. Họ nhìn thấy con quái vật Marfan đang tấn công cô bé Emily, thế nên họ bảo vệ cô với siêu âm tim và lệnh không cho chơi thể thao nữa. Họ còn lo lắng đến cả con cái sau này của Emily bởi chúng cũng sẽ có 50% nguy cơ bị Marfan. Cuộc đời của Emily như là một đường thẳng chỉ bắt đầu ngay từ đây, đúng chỗ này, với chẩn đoán Marfan. Đường thẳng ấy sẽ chỉ chạy đến tương lai với những nguy cơ tiềm ẩn, con ốm tiềm ẩn. Các bạn sinh viên của tôi chạy tuốt đến thì tương lai của Emily và mắc lại ở đó.

But Emily's life does not start there. It started eight years ago when her dad's sperm fused with her mom's egg, creating her very first cell. When they did that, they merged their chromosomes: 23 from dad, 23 from mom. They made 23 very loving chromosome couples in Emily's first cell. As this first cell multiplied, every cell after it would have an identical set of chromosomes made from the Original Twenty Three Pairs. These cells sculptured Emily's hands, feet, heart, and everything else. After she came out to the world and started growing up, more cells were made, each still contained the same chromosome set made faithfully identical to the Original Twenty Three Pairs.

Nhưng cuộc sống của Emily đâu có bắt đầu từ đó. Nó đã bắt đầu từ tám năm trước, khi một tinh trùng của cha cô bé hòa vào trứng của mẹ cô, tạo ra tế bào đầu tiên của cô bé. Khi tinh trùng và trứng gặp nhau, các nhiễm sắc thể (NST) cũng trộn vào một khối: 23 chiếc từ cha, 23 chiếc từ mẹ. Các NST ấy làm thành 23 cặp quấn quýt với nhau trong tế bào đầu tiên của Emily. Khi tế bào này nhân lên, mỗi tế bào con cháu chắt chút chít sau đó đều sẽ có một bộ NST giống y hệt như Hai Mươi Ba Đôi Đầu Tiên. Những tế bào này sẽ tạo nên hình hài của Emily, từ chân tay đến trái tim và tất cả những thứ khác. Sau khi cô bé ra đời rồi dần lớn lên, cơ thể cô sẽ làm ra nhiều tế bào hơn nữa, nhưng mỗi tế bào ấy vẫn mang theo một bộ NST giống y hệt như Hai Mươi Ba Đôi Đầu Tiên.

Chromosomes are not only loving couples who always want to be in pairs, they are also packages of genes. Because chromosomes stay in pair, the genes also stay in pairs. If chromosomes are trains, genes are very cheesy couples who always book exactly the same seats even when their trains depart from different stations. If a gene boards seat 15S on a train from mom, her partner gene will board seat 15S on the partner train from dad. When the trains meet in Emily's cell, they can line up perfectly with each other, and so can their genes: twenty thousand pairs of genes, each has one from dad and one from mom.

Nhiễm sắc thể (NST) không chỉ đơn thuẩn là các cặp đôi quấn quýt trong tế bào, chúng còn là hòm chứa gien. Bởi vì NST luôn làm thành cặp, gien cũng làm thành cặp luôn. Nếu ta coi NST như tàu hỏa thì gien giống như những cặp yêu nhau thắm thiết, luôn phải mua vé ngồi đúng một chỗ, mặc dù chuyến tàu họ đi xuất phát từ hai ga khác nhau. Nếu một gien lên ngồi ghế số 15S trên tàu từ ga mẹ, cái gien cặp đôi với nó sẽ lên ngồi ghế số 15S trên tàu từ ga bố. Khi những chuyến tàu NST này gặp nhau trong tế bào của Emily, chúng có thể xếp thành cặp đôi hoàn hảo với nhau, các gien trên tàu cũng thế. Hai mươi nghìn cặp gien, mỗi cặp gồm một chiếc từ cha và một chiếc từ mẹ.

It doesn't require a whole lot of fancy science to see that all of Emily's genes must have come from either her mom or her dad. Monolids? Definitely from dad. Thick black hair? Totally mom's. What about Marfan? Marfan happens because Emily has a faulty gene that refuses to make normal connective tissue proteins. That gene, too, of course, must have come from either her mom or her dad.

Không cần đến khoa học gì cao siêu, ta cũng có thể thấy là tất cả gien của Emily đều từ cha hoặc mẹ cô bé mà ra. Mắt một mí? Nhất định là từ bố. Tóc đen dầy? Rõ ràng là của mẹ. Thế còn Marfan thì sao? Marfan là do Emily có một gien bị lỗi. Gien ấy không chịu làm ra protein bình thường cho mô liên kết. Cái gien đấy tất nhiên là cũng phải từ cha hoặc mẹ mà ra.

How do we know which of her parents has that faulty gene? Well, years ago we didn't have anyway to know that (now we do, but more on that later). Doctors would have to look at them very carefully and see who has Marfan's symptoms. That person's aorta would be monitored to catch any early signs of Marfan's funny business. If someone had checked, they would have seen that Emily's mom is tall and lanky, her arms and legs unusually long, her fingers funny looking. She had signs of Marfan.

Làm sao ta biết được bố hay mẹ Emily mang gien lỗi ấy? Ờ, từng ấy năm trước thì ta chẳng có cách nào biết được cả (bây giờ thì có, nhưng chủ đề này để lúc khác tôi sẽ bàn tiếp). Bác sỹ phải khám cả hai để xem xem ai có dấu hiệu Marfan. Người đó sẽ phải đi khám và siêu âm tim định kỳ để nếu Marfan có gây sự vụ gì với tim mạch thì bác sỹ sẽ phát hiện ra sớm. Nếu như có ai để ý, họ sẽ thấy rằng mẹ của Emily cũng cao gầy, cũng có chân tay dài và ngón tay trông khác thường. Mẹ cô bé có dấu hiệu Marfan.

And it doesn't stop there. If Emily has any siblings, they have to be checked, too, for they might have gotten the faulty gene from her mom (there is a 50% chance that they did). Emily's mom might have gotten this gene from one of her parents - Emily's grandparents - who might have passed it on to any of their children other than Emily's mom. Now we have to check Emily's uncles and aunts. And then if any of them have Marfan, they might have passed it on to their own children - Emily's cousins. In short, all blood relatives on Emily's mother side must be checked for Marfan. They are all at risk of being killed by a ruptured aorta until they are confirmed to be Marfan-free, or until they are diagnosed and monitored.

Chuyện không phải chỉ đến đấy là hết. Nếu Emily có anh chị em ruột, họ cũng phải đi khám, bởi vì họ cũng có khả năng đã bị di truyền gien Marfan từ mẹ (khả năng là 50%). Mẹ của Emily có thể đã bị di truyền gien này từ bố hoặc mẹ của mình, tức là ông bà ngoại của Emily. Nếu đúng thế, ông bà ngoại của Emily có thể đã truyền gien này cho con cái của họ, không chỉ có mẹ của Emily. Bây giờ ta phải khám cả Emily cô dì chú bác bên ngoại. Nếu bất kỳ ai trong số họ bị Marfan, họ cũng có thể truyền gien bệnh này cho con cái họ, tức là anh chị em họ bên ngoại của Emily. Tóm lại, tất cả họ hàng ruột thịt bên ngoại của Emily phải được khám xem có bị Marfan hay không. Bởi vì, tất cả những người này đều có nguy cơ chết người do bóc tách động mạch chủ, và nguy cơ ấy chỉ có thể bị loại bỏ khi họ chắc chắn là không bị Marfan, hoặc là được chẩn đoán có Marfan và được kiểm tra thường xuyên.

My students don't see this risk. Somehow they worry Emily's hypothetical children yet forget about her currently living family members. They are very upset when I tell them Emily's mother died 5 years later of aorta rupture, undiagnosed. I hope they remember it. By the time another 8-year-old girl walks into their office with dislocated lenses, they will remember to check her mother.

Sinh viên của tôi không nhìn thấy nguy cơ ấy. Họ lo lắng cho con cái sau này của Emily nhưng lại quên mất những người thân và họ hàng ruột thịt đang sống sờ sờ ra của cô bé. Họ rất buồn khi tôi bảo rằng 5 năm sau thì mẹ Emily mất do bóc tách động mạch chủ mà không được chẩn đoán. Tôi chỉ mong rằng họ sẽ nhớ bài học này. Đến khi có một cô bé tám tuổi bị lệch thủy tinh thể bước vào phòng khám của họ, họ sẽ nhớ khám cho cả mẹ cô bé nữa.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

To be continued, maybe. This writing business is exhausting.

Chắc là còn tiếp. Viết lách mệt quá.

"Emily là một cô bé tám tuổi, gần đây vừa được chẩn đoán mắc hội chứng Marfan. Hội chứng Marfan là một tật di truyền trội, do đột biến gien mã hóa protein mô liên kết (như fibrillin hay collagen) gây ra. Các dấu hiệu thường gặp của hội chứng này là tạng người cao gầy, lệch thủy tinh thể, khớp biến dạng hoặc linh động, dễ mắc bệnh phổi. Emily có tất cả các dấu hiệu trên.

Bệnh nhân Marfan có nguy cơ giãn và bóc tách động mạch. Đây là một biến chứng rất nguy hiểm và có thể gây tử vong (40% bệnh nhân Marfan tử vong ngay lập tức khi bị bóc tách động mạch, nguy cơ tử vong tăng 1% đến 3% mỗi giờ sau khi động mạch bắt đầu bóc tách). Bệnh nhân phải tránh hoạt động mạnh và các môn thể thao cường độ cao để tránh gây thêm áp lực lên tim mạch. Siêu âm tim thường xuyên cho phép phát hiện các dấu hiệu bất thường của động mạch từ rất sớm. Chỉ định thuốc Losartan có thể làm giảm mức độ giãn động mạch. Nếu cần thiết, có thể chỉ định phẫu thuật trước khi động mạch bóc tách, làm giảm nguy cơ tử vong xuống thấp hơn 2%.

Nhóm của bạn gồm có một bác sỹ đa khoa, một chuyên gia tư vấn di truyền, và một bác sỹ chuyên môn tùy bạn chọn. Nhóm này được giao chăm sóc sức khỏe cho Emily và gia đình cô bé. Hãy soạn một liệu trình giám sát và điều trị, đồng thời giải thích cho bệnh nhân và gia đình."

Then I watch them jump into discussion. You might as well imagine that you are watching a movie here. My students are the hero going into a mysterious landscape to fight a dragon, rescue everyone and save their lives. As movie audience, you gasp when the hero almost fall off a cliff and you yell when they tumble into obvious traps. "You miss the mother! The dragon got her! Save her! No, don't go, come back, save her!" Such an obvious trap, you sigh.

Rồi tôi ngồi xem các bạn ấy xông vào thảo luận. Bạn đọc có thể tưởng tượng như là chúng ta đang xem phim vậy. Sinh viên của tôi là siêu nhân xông vào một vùng đất bí hiểm để chiến đấu với quái vật và giải cứu con tin. Là người xem, bạn có khi sẽ hết hồn khi siêu nhân suýt nữa thì rơi xuống vực, và bạn có khi sẽ cáu ầm lên khi họ rơi vào những cạm bẫy rõ lù lù ra là bẫy. "Quên mất bà mẹ rồi kìa! Con quái vật bắt được bà mẹ rồi! Cứu bà mẹ đi! Quay lại đằng sau, cứu bà mẹ!" Bẫy rõ lù lù ra thế mà, bạn thở dài.

Let's be fair: my students haven't read my blog. They have no clue how the movie would turn out. They are in it. They are in a maze of genes and mutations and pedigrees. They see Marfan the Dragon coming for Emily, and they protect her with echo and orders to stay away from sports. They brandish their weapons of Losartan and surgeries. They worry about Emily's hypothetical children who would have 50% chance of getting Marfan. Emily's life is a straight line that starts here, now, with her diagnosis of Marfan, and it will only go into the future with possible complications and possible sick children. It is the future of Emily that they travel to and get stuck in.

Công bằng mà nói, sinh viên của tôi đã đọc blog này đâu. Họ đâu biết kết cục phim sẽ như thế nào. Họ đang ở trong phim kìa. Họ lạc trong một mê cung với gien rồi đột biến rồi bảng phả hệ. Họ nhìn thấy con quái vật Marfan đang tấn công cô bé Emily, thế nên họ bảo vệ cô với siêu âm tim và lệnh không cho chơi thể thao nữa. Họ còn lo lắng đến cả con cái sau này của Emily bởi chúng cũng sẽ có 50% nguy cơ bị Marfan. Cuộc đời của Emily như là một đường thẳng chỉ bắt đầu ngay từ đây, đúng chỗ này, với chẩn đoán Marfan. Đường thẳng ấy sẽ chỉ chạy đến tương lai với những nguy cơ tiềm ẩn, con ốm tiềm ẩn. Các bạn sinh viên của tôi chạy tuốt đến thì tương lai của Emily và mắc lại ở đó.

But Emily's life does not start there. It started eight years ago when her dad's sperm fused with her mom's egg, creating her very first cell. When they did that, they merged their chromosomes: 23 from dad, 23 from mom. They made 23 very loving chromosome couples in Emily's first cell. As this first cell multiplied, every cell after it would have an identical set of chromosomes made from the Original Twenty Three Pairs. These cells sculptured Emily's hands, feet, heart, and everything else. After she came out to the world and started growing up, more cells were made, each still contained the same chromosome set made faithfully identical to the Original Twenty Three Pairs.

Nhưng cuộc sống của Emily đâu có bắt đầu từ đó. Nó đã bắt đầu từ tám năm trước, khi một tinh trùng của cha cô bé hòa vào trứng của mẹ cô, tạo ra tế bào đầu tiên của cô bé. Khi tinh trùng và trứng gặp nhau, các nhiễm sắc thể (NST) cũng trộn vào một khối: 23 chiếc từ cha, 23 chiếc từ mẹ. Các NST ấy làm thành 23 cặp quấn quýt với nhau trong tế bào đầu tiên của Emily. Khi tế bào này nhân lên, mỗi tế bào con cháu chắt chút chít sau đó đều sẽ có một bộ NST giống y hệt như Hai Mươi Ba Đôi Đầu Tiên. Những tế bào này sẽ tạo nên hình hài của Emily, từ chân tay đến trái tim và tất cả những thứ khác. Sau khi cô bé ra đời rồi dần lớn lên, cơ thể cô sẽ làm ra nhiều tế bào hơn nữa, nhưng mỗi tế bào ấy vẫn mang theo một bộ NST giống y hệt như Hai Mươi Ba Đôi Đầu Tiên.

Chromosomes are not only loving couples who always want to be in pairs, they are also packages of genes. Because chromosomes stay in pair, the genes also stay in pairs. If chromosomes are trains, genes are very cheesy couples who always book exactly the same seats even when their trains depart from different stations. If a gene boards seat 15S on a train from mom, her partner gene will board seat 15S on the partner train from dad. When the trains meet in Emily's cell, they can line up perfectly with each other, and so can their genes: twenty thousand pairs of genes, each has one from dad and one from mom.

Nhiễm sắc thể (NST) không chỉ đơn thuẩn là các cặp đôi quấn quýt trong tế bào, chúng còn là hòm chứa gien. Bởi vì NST luôn làm thành cặp, gien cũng làm thành cặp luôn. Nếu ta coi NST như tàu hỏa thì gien giống như những cặp yêu nhau thắm thiết, luôn phải mua vé ngồi đúng một chỗ, mặc dù chuyến tàu họ đi xuất phát từ hai ga khác nhau. Nếu một gien lên ngồi ghế số 15S trên tàu từ ga mẹ, cái gien cặp đôi với nó sẽ lên ngồi ghế số 15S trên tàu từ ga bố. Khi những chuyến tàu NST này gặp nhau trong tế bào của Emily, chúng có thể xếp thành cặp đôi hoàn hảo với nhau, các gien trên tàu cũng thế. Hai mươi nghìn cặp gien, mỗi cặp gồm một chiếc từ cha và một chiếc từ mẹ.

It doesn't require a whole lot of fancy science to see that all of Emily's genes must have come from either her mom or her dad. Monolids? Definitely from dad. Thick black hair? Totally mom's. What about Marfan? Marfan happens because Emily has a faulty gene that refuses to make normal connective tissue proteins. That gene, too, of course, must have come from either her mom or her dad.

Không cần đến khoa học gì cao siêu, ta cũng có thể thấy là tất cả gien của Emily đều từ cha hoặc mẹ cô bé mà ra. Mắt một mí? Nhất định là từ bố. Tóc đen dầy? Rõ ràng là của mẹ. Thế còn Marfan thì sao? Marfan là do Emily có một gien bị lỗi. Gien ấy không chịu làm ra protein bình thường cho mô liên kết. Cái gien đấy tất nhiên là cũng phải từ cha hoặc mẹ mà ra.

How do we know which of her parents has that faulty gene? Well, years ago we didn't have anyway to know that (now we do, but more on that later). Doctors would have to look at them very carefully and see who has Marfan's symptoms. That person's aorta would be monitored to catch any early signs of Marfan's funny business. If someone had checked, they would have seen that Emily's mom is tall and lanky, her arms and legs unusually long, her fingers funny looking. She had signs of Marfan.

Làm sao ta biết được bố hay mẹ Emily mang gien lỗi ấy? Ờ, từng ấy năm trước thì ta chẳng có cách nào biết được cả (bây giờ thì có, nhưng chủ đề này để lúc khác tôi sẽ bàn tiếp). Bác sỹ phải khám cả hai để xem xem ai có dấu hiệu Marfan. Người đó sẽ phải đi khám và siêu âm tim định kỳ để nếu Marfan có gây sự vụ gì với tim mạch thì bác sỹ sẽ phát hiện ra sớm. Nếu như có ai để ý, họ sẽ thấy rằng mẹ của Emily cũng cao gầy, cũng có chân tay dài và ngón tay trông khác thường. Mẹ cô bé có dấu hiệu Marfan.

And it doesn't stop there. If Emily has any siblings, they have to be checked, too, for they might have gotten the faulty gene from her mom (there is a 50% chance that they did). Emily's mom might have gotten this gene from one of her parents - Emily's grandparents - who might have passed it on to any of their children other than Emily's mom. Now we have to check Emily's uncles and aunts. And then if any of them have Marfan, they might have passed it on to their own children - Emily's cousins. In short, all blood relatives on Emily's mother side must be checked for Marfan. They are all at risk of being killed by a ruptured aorta until they are confirmed to be Marfan-free, or until they are diagnosed and monitored.

Chuyện không phải chỉ đến đấy là hết. Nếu Emily có anh chị em ruột, họ cũng phải đi khám, bởi vì họ cũng có khả năng đã bị di truyền gien Marfan từ mẹ (khả năng là 50%). Mẹ của Emily có thể đã bị di truyền gien này từ bố hoặc mẹ của mình, tức là ông bà ngoại của Emily. Nếu đúng thế, ông bà ngoại của Emily có thể đã truyền gien này cho con cái của họ, không chỉ có mẹ của Emily. Bây giờ ta phải khám cả Emily cô dì chú bác bên ngoại. Nếu bất kỳ ai trong số họ bị Marfan, họ cũng có thể truyền gien bệnh này cho con cái họ, tức là anh chị em họ bên ngoại của Emily. Tóm lại, tất cả họ hàng ruột thịt bên ngoại của Emily phải được khám xem có bị Marfan hay không. Bởi vì, tất cả những người này đều có nguy cơ chết người do bóc tách động mạch chủ, và nguy cơ ấy chỉ có thể bị loại bỏ khi họ chắc chắn là không bị Marfan, hoặc là được chẩn đoán có Marfan và được kiểm tra thường xuyên.

My students don't see this risk. Somehow they worry Emily's hypothetical children yet forget about her currently living family members. They are very upset when I tell them Emily's mother died 5 years later of aorta rupture, undiagnosed. I hope they remember it. By the time another 8-year-old girl walks into their office with dislocated lenses, they will remember to check her mother.

Sinh viên của tôi không nhìn thấy nguy cơ ấy. Họ lo lắng cho con cái sau này của Emily nhưng lại quên mất những người thân và họ hàng ruột thịt đang sống sờ sờ ra của cô bé. Họ rất buồn khi tôi bảo rằng 5 năm sau thì mẹ Emily mất do bóc tách động mạch chủ mà không được chẩn đoán. Tôi chỉ mong rằng họ sẽ nhớ bài học này. Đến khi có một cô bé tám tuổi bị lệch thủy tinh thể bước vào phòng khám của họ, họ sẽ nhớ khám cho cả mẹ cô bé nữa.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

To be continued, maybe. This writing business is exhausting.

Chắc là còn tiếp. Viết lách mệt quá.

Thứ Hai, 22 tháng 2, 2016

My Marfan tale, Part 2: Broken heart

Câu chuyện Marfan của tôi, Phần 2: Đau lòng

The doctors at Children's were indeed good at this stuff. They gave me a diagnosis: Marfan syndrome.

I don't remember how the diagnosis came about, but that wasn't important at the time. The important thing was to find out what it was and how to deal with it. It was like going to the doctor to ask why your nose kept running even though you had taken all the NyQuil you could. We wanted to know why my eyes were different, why I couldn't just put on a pair of glasses like virtually two third of my class and let my parents blame television for ruining my generation's vision. The doctors at Children's had the superpower to solve this mystery. Marfan was a straightforward, convenient answer to all the questions regarding my eyes, most often directed at my parents. "Why do you let her read so up close?" "She has Marfan." "Why don't you get her glasses?" "She has Marfan." "Why don't you fix her eyes?" "She has Marfan."

Các bác sỹ ở viện Nhi đúng là giỏi mấy cái này. Họ chẩn đoán là tôi mắc hội chứng Marfan.

Tôi không nhớ việc chẩn đoán diễn ra như thế nào, nhưng lúc ấy cái đó không quan trọng. Cái quan trọng là phải tìm ra tôi bị làm sao và phải điều trị như thế nào. Cái này cũng giống như việc đi khám bác sỹ để hỏi vì sao cứ bị sổ mũi mãi không khỏi, mặc dù đã uống Decolgen các kiểu rồi. Gia đình tôi muốn biết vì sao mắt tôi bị như vậy, vì sao tôi không thể đeo kính bình thường giống như hai phần ba các bạn cùng lớp và để phụ huynh chúng tôi được thoải mái phàn nàn là ti vi làm hỏng hết mắt bọn trẻ. Các bác sỹ ở viện Nhi có khả năng phi thường để giải đáp bí ẩn đó. Marfan là một cách trả lời đơn giản tiện lợi cho tất tất cả các câu hỏi liên quan đến mắt của tôi mà thường ba mẹ tôi là người bị hỏi. “Vì sao lại để cho nó đọc gần như thế?” “Nó bị Marfan.” “Vì sao không cho nó đeo kính?” “Nó bị Marfan.” “Sao không chữa mắt cho nó?” “Nó bị Marfan.”

Nothing could fix Marfan, it so seemed. We were told that I must avoid contact sport and demanding physical activities, and I must have regular checkups. These orders hardly bothered me for I had never been an athletic kid. They probably bothered my parents, both of whom were very active and fit and had always tried to make me more like them. Now they had to let me curl up with my books. Not only had Marfan rescued my parents from uninvited comments regarding their parenting methods, it also excused me from expectations that I never meant to meet. Everyone was happy.

Dường như không có cách nào chữa khỏi Marfan được cả. Gia đình tôi được lệnh là tôi phải tránh các môn thể thao và vận động mạnh, đồng thời phải đi khám định kỳ. Những việc này tôi đều không thấy phiền, tôi vốn không ham thích thể thao. Ba mẹ tôi thì có lẽ thấy hơi phiền vì cả hai người đều thích vận động và luôn muốn tôi noi gương họ. Bây giờ thì ba mẹ tôi đành phải để tôi nằm nhà đọc sách. Marfan không chỉ là một phương tiện để cho ba mẹ tôi tránh người ngoài bới móc việc họ nuôi dạy tôi ra sao, mà còn cho tôi một cái cớ để không phải phấn đấu đạt những nguyện vọng tôi không tha thiết. Vì thế, ai cũng vừa lòng.

Almost everyone. My mother was constantly upset over my status of having Marfan. She refused to believe that I was okay with not running around playing soccer. She thought it was terribly unfair that the content of my classroom’s chalkboard was invisible to me, and that it was her job to make up for it. She flung herself into fruitless meetings and talks with my teachers and doctors to get me the best seat possible. When the teachers finally gave up and moved me to the front row, she would ask me if it helped in such a desperately hopeful voice that I felt obligate to say it did (it did not). She took me to checkups every three months. She took complete responsibility for the fact that I had to get up early, wait in a long line, let people poke me in the eyes, let people put gluey gel on my chest for an echocardiogram, get exhausted from being tossed from one clinic to the next. She constantly petted me the way one pets a terrified cat at the vet, apologized for everything, and rewarded me to my favorite food after the countless examinations were over. She always said it was unfair that I ended up with all the bad luck while everyone else was fine. It was like I happened to walk by when the gods were spraying Bad Luck and got a full blast, and my mother felt guilty that she could not protect me from it.

Hầu như ai cũng vừa lòng. Mẹ tôi lúc nào cũng thấy phiền lòng vì việc tôi mắc hội chứng Marfan. Mẹ không chịu tin là tôi hoàn toàn không thiết tha việc chạy nhảy chơi bóng đá. Mẹ cho rằng tôi phải đi học mà không nhìn thấy bảng thì rất bất công, và đấy là việc của mẹ là phải làm cho ra nhẽ. Mẹ tôi sẽ tìm cách gặp nói chuyện với các thầy cô giáo và các bác sỹ để tìm cách chuyển chỗ ngồi trong lớp cho tôi. Khi các cô giáo đầu hàng và cho tôi lên ngồi bàn đầu, mẹ sẽ hỏi tôi chỗ mới có khá hơn không với một giọng đầy hy vọng, làm cho tôi đành phải nói là có (thực ra là không, tôi vẫn không nhìn thấy bảng viết gì). Mẹ đưa tôi đi khám ba tháng một lần. Mẹ chịu trách nhiệm với việc tôi phải dậy sớm, xếp hàng chờ lâu, bị chọc vào mắt, bị bôi keo lên ngực để siêu âm, bị mệt vì phải chạy từ phòng khám này sang phòng khám khác. Mẹ dỗ dành tôi như kiểu người ta dỗ mèo ở phòng khám thú y, xin lỗi đủ thứ, rồi đưa tôi đi ăn món tôi thích nhất sau buổi khám. Mẹ tôi luôn bảo rằng tôi bị thiệt thòi vì phải hứng hết vận đen, trong khi mọi người trong nhà không ai làm sao cả. Nghe cứ như thể tôi chẳng may đi qua lúc trời phật đang phun Vận Đen và hứng trọn một gáo, và mẹ tôi thấy có lỗi vì không che chở được cho tôi.

My mother died in 2000, five years after my diagnosis of Bad Luck. She had a heart attack. She was doing laundry when she had a terrible chest pain. We took her to the hospital. The doctors shook their heads and said she has a tear in her aorta. The fancy word was “aorta aneurysm”. There was nothing they could do. She stayed in the hospital for ten weeks and we watched as everything that was made of her left. She was tall, stunningly beautiful, her laughter loud and contagious. She lost weight until she was the size of a skinny ten year old. The extreme pain episodes came more often and took her consciousness away. Her speech went next. She could not call me or my brother. She made some sound that resembled a baby learning to talk, we knew what she meant but we could not hear what she said. Even then, she was so determined to live. She wanted to be transferred to France. She wanted to try everything. So we did. But nothing, even her enormous determination and optimism, was enough to reverse the tear in her aorta.

Mẹ tôi mất năm 2000, tức là 5 năm sau khi tôi được chẩn đoán. Mẹ bị đau tim. Hôm đó mẹ tôi đang giặt quần áo thì bỗng nhiên thấy rất đau ở ngực. Gia đình tôi đưa mẹ vào bệnh viện. Các bác sỹ lắc đầu, nói rằng động mạch chủ của mẹ bị rò. Từ chuyên môn là “bóc tách động mạch chủ”. Họ không thể làm gì hơn được. Mẹ tôi nằm viện 10 tuần, trong khi chúng tôi nhìn mẹ ngày một yếu đi. Mẹ vốn rất cao, rất xinh đẹp, có giọng cười to và dễ làm người khác cười theo. Mẹ sụt cân cho đến khi chỉ còn trông như một cô bé 10 tuổi gầy nhom. Những cơn đau kéo đến thường xuyên hơn, và mẹ không còn tỉnh táo nữa. Sau đó là tiếng nói. Mẹ tôi không còn gọi được tên tôi hoặc tên em trai tôi. Mẹ phát ra những âm thanh như trẻ con đang tập nói, chúng tôi hiểu được mẹ muốn nói gì, nhưng không nghe được từ nào. Nhưng dù thế nào, mẹ vẫn nhất định muốn sống. Mẹ muốn được đưa đi Pháp chữa bệnh, muốn được thử các phương thức điều trị mới. Gia đình tôi thử hết mọi cách. Đến cuối cùng, không có cách nào cứu vãn được vết rách động mạch chủ của mẹ, ngay cả nghị lực và lòng lạc quan phi thường của mẹ cũng không.

After my mother’s death, life was rough for all of us. We were now a helpless family of a single father, a new teenager, and a four year old. A very young, strong-willed woman joined us a year later and became my stepmother two years after that. We were all busy wrangling the family, and Marfan was pushed to the side and almost forgotten. I had a handful of checkups in five years. I was used to my bad vision; I could handle classes without seeing the board. My friends took me to school and back home so that I would not crash into things. They accepted Marfan as a part of me and asked no more about it. The peak of interest in Marfan that I received from my friends was when one girl pointed out a line in our genetics textbook that said “Marfan syndrome is linked to a dominant mutation on chromosome 15.”

Sau khi mẹ tôi mất, cuộc sống trở nên khó khăn hơn. Gia đình tôi bây giờ gồm có một ông bố đơn thân, một cô bé mới dậy thì, và một cậu bé bốn tuổi. Một phụ nữ rất trẻ với cá tính rất mạnh gia nhập vào nhà tôi một năm sau đó, rồi hai năm sau trở thành mẹ kế của chúng tôi. Mọi người đều bận rộn tìm cách duy trì cuộc sống gia đình, Marfan gần như bị quên lãng. Tôi đi khám một đôi lần trong vòng 5 năm tiếp theo. Tôi đã quen với thị lực của mình, tôi có thể đi học mà không cần nhìn bảng. Các bạn tôi đi kèm tôi từ nhà đến trường rồi từ trường về nhà để đảm bảo là tôi không đâm vào đâu. Bạn bè tôi coi Marfan là một phần của tôi, và không hỏi thêm gì nữa. Có một lần, một người bạn cùng lớp chỉ cho tôi một dòng trong sách Di truyền học “Hội chứng Marfan liên quan đến một đột biến trội trên nhiễm sắc thể số 15.”

After my first year of college, I took a trip to visit my aunt in Saigon. Knowing about my eyes, she insisted to take me to a checkup. But first, I had to explain to her what it was to be checked.

“My lenses are dislocated.” I said.

“Why?” She asked.

“I don’t know. I have this thing called Marfan syndrome. They told me to not run and do heavy sports.” I shrugged and reported the one thing I knew about my condition.

“Why not? Would running knock your lenses out of your eyes or something?” She kept on.

“I don’t know. I don’t think it works that way.”

“So how does it work?”

Sau năm nhất đại học, tôi vào thăm dì tôi trong Sài Gòn. Dì biết mắt tôi kém và đòi đưa tôi đi khám. Nhưng trước hết, tôi phải giải thích cho dì hiểu là khám cái gì đã.

“Mắt cháu bị lệch thủy tinh thể.” Tôi nói.

“Tại sao lại thế?” Dì hỏi.

“Cháu cũng không biết. Cháu bị hội chứng Marfan. Người ta bảo cháu không được chạy và không được chơi thể thao.” Tôi báo cáo điều duy nhất tôi biết về bệnh của mình.

“Sao lại không được chơi thể thao? Chạy nhảy thì cái thủy tinh thể nó rơi ra à?” Dì tiếp tục hỏi.

“Cháu không biết. Cháu không nghĩ thế.”

“Thế thì là như thế nào?”

I didn’t know the answer to that question. No one ever asked me that. I never asked anyone that. I lived with Marfan as a normal part of my life and did not question what it really was. On my aunt’s computer, I went to google about Marfan for the first time, ten years after my diagnosis. There wasn’t much about it even on the Internet, and my English wasn’t good enough to read. I picked a short Vietnamese article on a casual online magazine. I am only recalling it from my memory now.

“Marfan syndrome is a genetic disorder that affects the connective tissues. The typical symptoms are tall and lanky stature, dislocated lenses, double joints, lungs complications, and most seriously, aorta aneurysm.”

Tôi không biết trả lời dì như thế nào. Chưa từng có ai hỏi tôi thế cả. Tôi cũng chưa từng hỏi ai bao giờ. Tôi mặc nhiên chấp nhận Marfan mà chưa từng thắc mắc nó là cái gì. Dùng máy tính của dì, lần đầu tiên tôi lên mạng google về Marfan, lúc nào là mười năm sau khi tôi được chẩn đoán. Ngay cả trên mạng cũng không có nhiều thông tin về bệnh này, mà tiếng Anh của tôi lúc đó thì chưa tốt. Tôi mở một bài báo tiếng Việt đăng trên một tạp chí mạng. Nội dung sau đây là từ trí nhớ của tôi mà ra.

“Hội chứng Marfan là một tật di truyền làm biến đổi mô liên kết. Các triệu chứng điển hình bao gồm tạng người cao gây, lệch thủy tinh thể, khớp mềm và linh động, các bệnh phổi, và nghiêm trọng nhất là bóc tách động mạch chủ.”

Aorta aneurysm.

All of sudden, it hit. My mother had Marfan syndrome and died from it. She had the same mutation on chromosome 15 that got passed on to me, and this same mutation messed up our connective tissues. That was why we were both tall and lanky – connective tissues made up the bones and joints. That was why my lenses were dislocated – connective tissues held them in place. That was why her aorta broke – connective tissues made up blood vessels. That was why the doctors had told me to not play sports: they did not want my aorta to break. That was also why I had regular echocardiograms, so that any funny business around the aorta would be detected early. I did not get the full blast of Bad Luck, my dislocated lenses gave the obvious but not deadly sign of Marfan, and I was protected from its more vicious attacks. My mother did not know it was coming for her, too. She got the full blast.

Bóc tách động mạch chủ.

Bỗng nhiên mọi thứ trở nên sáng tỏ. Mẹ tôi bị hội chứng Marfan và mất cũng vì bệnh này. Mẹ mang trong người cùng một đột biến trên nhiễm sắc thể số 15, và đột biến ấy di truyền sang tôi. Cũng một đột biến ấy đã làm biến đổi mô liên kết của cả mẹ và tôi. Đấy là lý do vì sao cả hai chúng tôi đều cao và gầy – mô liên kết là cái làm nên xương và khớp. Đấy cũng là lý do vì sao thủy tinh thể của tôi bị lệch – mô liên kết giữ cho thủy tinh thể ở đúng vị trí. Cũng vì lý do này mà động mạch chủ củ mẹ bị rò – mô liên kết làm nên các mạch máu trong người. Đây cũng là lý do các bác sỹ bảo tôi không được vận động mạnh: để tránh làm hại đến động mạch chủ. Tôi phải đi khám và siêu âm tim đều đặn để nếu có sự gì xảy ra với động mạch chủ, người ta sẽ phát hiện ra sớm. Tôi không bị hứng trọn Vận Đen, thủy tinh thể của tôi bị lệch là triệu chứng rõ ràng nhưng không đến mức gây chết người của hội chứng Marfan. Vì có triệu chứng đó mà những rủi ro lớn hơn đã được phòng ngừa. Mẹ tôi không hề hay biết mẹ cũng mang bệnh. Những rủi ro đó đổ ập lên mẹ.

Years later, I still wonder what it would have been like if we had known. What if my mother had been diagnosed and put on the precaution measures that I was on for years? Could we have delayed the aorta aneurysm a little while? Could we have detected the tear a little earlier, a smaller and manageable tear? Could we have bought some time for medical science to develop a treatment for small aorta aneurysm, which it did, and saved her? The questions snowball into a helpless feeling for the irreversible past. It is like I am forever swallowing a gigantic bite of a bitter and heavy substance. It hurts.

Nhiều năm sau, tôi vẫn tự hỏi nếu biết trước thì mọi việc sẽ thế nào. Nếu như mẹ tôi được chẩn đoán và được dặn dò phải cẩn thận và tránh vận động mạnh giống như tôi, hàng năm trước đó? Liệu như thế có làm chậm vết rò động mạch lại không? Liệu có thể phát hiện ra vết rò ấy sớm hơn, lúc nó còn nhỏ và cứu chữa được không? Liệu như thế có giữ cho động mạch của mẹ nguyên vẹn thêm một ít lâu nữa, đủ thời gian để y học tìm ra cách chữa trị động mạch bị bóc tách, để cứu được mẹ? Những câu hỏi như thế cứ chồng lên nhau thành một cảm giác bất lực về một quá khứ không thể nào thay đổi được. Cũng giống như tôi đang nuốt phải một cục gì rất to, nặng và đắng ngắt. Rất đau.

(to be continued)

(còn tiếp)

Thứ Hai, 15 tháng 2, 2016

My Marfan Tale, Part 1: The dislocated lenses

Câu chuyện Marfan của tôi, Phần 1: Lệch thể thủy tinh

(Dưới mỗi đoạn đều có dịch tiếng Việt)I tap the little triangle and a robotic voice comes out: "Hello, this the the Retina Institute. We are calling to remind Linh that you have an appointment scheduled for Friday, February 5th at 3:30 in the afternoon with Dr. Kevin Blinder at 226 South Woodmill Road Suite 50 West in Chesterfield located in the West building of Saint Luke Hospital on the fifth floor. Please bring your insurance card and a current list of medications. Please note we no longer accept cash payment..." The voice sounds strangely dreamy, as if its owner was still waking up from a nap when she was reading this note into a recorder. Every time there is a piece of actual information, like my name or the date and time of the appointment, a completely awake voice jumps in and announces it. I hang up, open my calendar, and mark my next ophthalmology appointment according to the awake voice.

Tôi bấm vào hình tam giác và nghe một giọng robot nói ra: "Xin chào, đây là Viện Võng mạc. Chúng tôi gọi để nhắc Linh là bạn có hẹn đến khám vào thứ 6 ngày mùng 5 tháng 2 vào lúc 3:30 chiều với bác sỹ Kevin Blinder ở số 226 đường Woodmill phòng 50 tầng 5 khu nhà phía Tây bệnh viện Thánh Luke. Xin nhớ mang thẻ bảo hiểm và đơn các loại thuốc đang dùng. Xin lưu ý cho là chúng tôi không nhận thanh toán tiền mặt..." Giọng nói này nghe mơ hồ một cách kỳ lạ, như thể chủ nhân của nó vẫn còn đang ngái ngủ khi đọc những dòng này vào máy thu âm. Mỗi khi có một mầu thông tin quan trọng như tên tôi hay ngày giờ của buổi hẹn khám, một giọng khác hoàn toàn tỉnh ngủ lại xen vào. Tôi dập máy, mở lịch và đánh dấu buổi khám mắt mà giọng tỉnh ngủ ấy vừa thông báo.

Seeing an ophthalmologist has been a regular part of my life since I was eight. Before then, I was an excellent first and second grader with little assistance. I was book-smart, quiet, well-behaved, my teachers' favorite, only capable of getting A's and A+'s. My parents had a tremendous shock when I got a F in the first test in third grade. Perhaps puberty hit early and caught them off guard, they thought. My mother sat me down for "the talk" and was immensely relieved to find out I just couldn't see the test questions, which were written on a big blackboard in front of the classroom, and was too shy to ask. My parents celebrated the no-puberty-yet discovery and happily blamed myopia for my F. My father was then assigned to take me to an optometrist.

Việc đi khám mắt là việc rất bình thường đối với tôi từ khi lên tám. Trước đó, năm lớp một và lớp hai tôi là học sinh xuất sắc mà không cần hỗ trợ gì. Tôi học vẹt giỏi, ít nói, ngoan, luôn là học sinh được các cô yêu thích, luôn được điểm cao. Ba mẹ tôi bị sốc nặng khi tôi bị điểm 2 trong bài kiểm tra đầu năm lớp 3. Có khi đây là dấu hiệu sớm của tuổi dậy thì dữ dội, ba mẹ tôi nghĩ. Mẹ tôi gọi tôi vào "nói chuyện" để sau đó thấy nhẹ cả người khi biết rằng tôi chỉ là không nhìn thấy đề bài trên bảng mà lại nhát không dám hỏi. Vui mừng vì chưa-có-tuổi-dậy-thì-nào-ở-đây-hết, ba mẹ tôi đổ tội điểm 2 cho tật cận thị. Ba tôi được giao nhiệm vụ đưa tôi đi đo mắt.

A simple distinction between an ophthalmologist and an optometrist: the latter does not poke you in the eyes. Not usually. My father took me to Trang Tien, which was the Optometry Street in Hanoi (everything in Hanoi clusters into their own street, so we have Leather Street, Fabric Street, Shoes Street, Dried Fruit Street, you name it. It is amazingly convenient.) No one can make a living from asking 8-year-old's to read off letters of different sizes, and so most optometry offices also sell glasses. My father proudly spent a large portion of his paycheck on a pair of bottle bases that would claim a prime location on my face and bring back the A's.

Cách phân biệt bác sỹ khám mắt và chuyên viên đo mắt: người đo mắt không chọc vào mắt bạn. Thường là không. Ba tôi đưa tôi đến Tràng Tiền, thời đó là Phố Đo Mắt ở Hà Nội (ở Hà Nội cái gì cũng có phố của nó: Phố Hàng Da, Phố Hàng Vải, Phố Hàng Giầy, Phố Hàng Ô Mai Mứt, tùy bạn chọn. Rất là tiện lợi.) Không ai có thể kiếm đủ sống chỉ bằng việc bảo trẻ con 8 tuổi đọc bảng chữ với các kích cỡ khác nhau, cho nên hầu hết các hàng đo mắt đều có bán kính. Ba tôi chi ra một phần lương tháng đáng kể để mua cho tôi một đôi đít chai mà một khi ngự lên mặt tôi sẽ chắc chắn mang những điểm 10 trở lại.

The glasses did claim my face for a whole day but did not have a chance to bring back my A's. My mother quickly noticed that I still could not read my books without holding them up to touch my nose. The clock on the opposite wall remained invisible to me. My vision did not change with the expensive Bottle Bases. The non-poking diagnosis on the Optometry Street did not work. We were going somewhere else.

Cặp kính đã ngự lên mặt tôi cả một ngày nhưng chưa có dịp mang những điểm 10 trở lại. Mẹ tôi nhanh chóng nhận ra rằng tôi vẫn phải dí mũi vào thì mới đọc được sách. Đồng hồ trên tường vẫn mờ như tàng hình. Thị lực của tôi không hề thay đổi dù có cặp Đít Chai đắt tiền. Cách chẩn đoán không cần chọc vào mắt trên Phố Đo Mắt không hiệu quả. Nhà tôi sẽ phải đi khám nơi khác.

"Somewhere else" was the Ophthalmology Institute, a medium-sized, overcrowded hospital specialized in all eye-related problems. There were no waiting room, so patients packed every open space waiting for their turn. The wait took forever. My mother and I arrived between 7 and 8 AM right after the clinic opened and the line was already long. The hallway smelled strongly of chlorine and faintly but definitely of pee. More than half of the crowd was children of all ages, with and without eye patches. By 11 AM, when Hanoi went out of its way to prove that it could get hotter and greasier, some of them were so tired they looked like very sulky pirates.

"Nơi khác" là Viện Mắt trung ương, một bệnh viện cỡ trung, đông bệnh nhân, chuyên các vấn đề về mắt. Ở đó không có phòng chờ, thế nên bệnh nhân chiếm đóng hết các khoảng không gian có thể để chờ đến lượt mình. Thời gian chờ lúc nào cũng rất lâu. Mẹ tôi đưa tôi đến viện khoảng tầm 7 hay 8 giờ sáng, ngay sau khi phòng khám mở cửa, thế mà người đã xếp thành một hàng dài. Hành lang phòng khám sặc mùi thuốc tẩy và thoảng mùi nước tiểu. Hơn nửa số người xếp hàng là trẻ con đủ mọi lứa tuổi, có đứa đeo băng mắt, có đứa không. Đến tầm 11 giờ trưa, khi Hà Nội gồng mình lên chứng tỏ là thời tiết ở đây vẫn còn có thể nóng nực hơn được nữa, mấy đứa trẻ con đã mệt nhoài và trông giống như một lũ cướp biển đang dỗi.

My name was called at last, sometimes after so long a wait that the dilate drops had expired and they had to dilate my eyes again. The nurse tried to tap what looked like a tiny hammer onto my pupils to measure my eye pressure. She was cranky because I could not "hold it open" and "look straight" and "hold still". "You try, lady", I thought, and used all the energy I had to fight against the instinct to close my eyes when the hammer came near, above it shone the bright fluorescent light.

Cuối cùng người ta cũng gọi tên tôi, thường là sau một khoảng thời gian chờ quá lâu nên thuốc giãn đồng tử đã hết tác dụng, người ta phải nhỏ giãn đồng tử lại lần thứ hai. Cô y tá tìm cách gõ một cái búa tí hon lên con ngươi của tôi để đo nhãn áp. Thường cô ấy sẽ phát cáu vì tôi không thể nào "mở to mắt ra" và "nhìn thẳng" và "giữ nguyên như thế". "Cô cứ thử đi thì biết", tôi nghĩ, và vận dụng hết công lực để chống lại phản xạ tự nhiên là nhắm mắt khi thấy cái búa dí lại gần, trên trần nhà ngự một bóng đèn sáng chói.

|

| The tiny hammer - Búa đo nhãn áp |

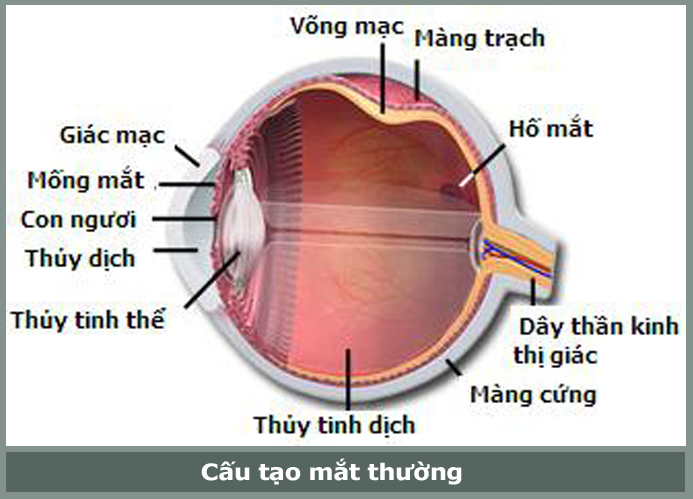

Rồi người ta tiếp tục soi vào mắt tôi với các loại đèn sáng chói để khám thể thủy tinh rồi dịch mắt rồi võng mạc. Võng mạc là một màng lưới rất mỏng ở phía lưng con mắt, có nhiệm vụ bắt ánh sáng và gửi tín hiệu cho não, từ đó não sẽ đoán ra hình thù, kích cỡ, màu sắc và khoảng cách của cái vật mà mắt đang nhìn thấy. Dịch mắt là một quả bóng chứa đầy một chất keo trong suốt, làm thành phần lớn con mắt. Thể thủy tinh là một miếng "kính" sống, bé xíu, có thể zoom gần xa để thu được một lượng ánh sáng tốt nhất cho võng mạc. Võng mạc và dịch mắt của tôi đều khỏe mạnh bình thường, nhưng thể thủy tinh thì không. Chúng không nằm đúng vị trí; chúng đã lệch lên phía trên và ra phía ngoài so với vị trí trong mắt bình thường. Chúng không thể thu ánh sáng đúng cách, vì thế nên thị lực của tôi mới kém như vậy. Cũng chính vì thế mà kính cận không giúp được gì cho tôi: họ không tính đến việc thể thủy tinh của tôi bị lệch. Ở phòng đo mắt, họ cho rằng thể thủy tinh của tôi nằm đúng vị trí, chỉ không zoom được gần xa mà thôi. Thực tế là, thể thủy tinh của tôi zoom tốt nhưng không chịu ở đúng nơi quy định.

But there was something else about the eight-year-old me, something more general than dislocated lenses. I was very tall and lanky. I was always a head taller than everyone else in my class (that was why my teachers couldn't just let me sit in the front row - I'd block everyone.) My fingers looked funny. My arms and legs looked strange. My ophthalmologist thought I might have had a rare disease, but he couldn't be sure. "Take her to Children's Hospital", he told my mother, "they're good at this stuff."

Nhưng vẫn còn có điều gì đó khác thường, một cảm giác chung chung hơn là chỉ có lệch thể thủy tinh. Tôi rất cao và gầy. Hồi đó tôi luôn là đứa cao nhất lớp, cao hơn chúng bạn một cái đầu (đấy cũng là lý do vì sao các cô giáo không thể cho tôi ngồi bàn đầu được, tôi sẽ che hết các bạn phía sau.) Ngón tay của tôi trông kỳ cục. Cẳng tay cẳng chân của tôi trông cũng lạ. Bác sỹ nhãn khoa cho là tôi mắc một bệnh hiếm gặp, nhưng ông không chắc chắn. "Đưa cháu sang viện Nhi nhé", ông bảo mẹ tôi, "ở bên ấy họ giỏi mấy cái này lắm."

(to be continued)

(còn tiếp)

Thứ Sáu, 5 tháng 2, 2016

A writing about writing - part 3

What do I write about?

I often don't have to hunt for writing topics, they sort of just fall onto my plate. The source of this luxury is not some extraordinary talent I possess, but rather mundane: I do something else for food (and bills). I let writing be as free as a bird: it doesn't have to carry deadlines, cranky bosses, lame coworkers, and worst of all, a dreadful purpose "I have to do this to pay the bills". It is my hobby. It's like basketball or video game or Facebook (none of these are hobbies of mine, but the point is, you don't think "Ugh, it's time to Facebook again, how I hate it! What am I gonna do here?")

Writing is easy to me because I can write whenever I want, about whatever I choose, in whatever style and length I feel like. When an idea pops into my head ("Let's write about writing!"), I walk around with it for a little while, collect random odds and ends that fall into the topic, then when I feel like it's time to write them down, I write them down. That's it. If you don't do that, writing is probably not your hobby. You don't do it for fun.

Not until recently have I realized that professional writers don't write for fun either. This is a very obvious fact if you think about it. They have to write for food. They have to pay their bills. They have to send their kids to school. They have to race deadlines. A lot of times they have to write about something they are not at all interested. Just like us with our jobs, they procrastinate and avoid doing it. Even when they get the writing done, they have to watch it torn apart by their editors, ignored by their readers, and forgotten inside a magazine or on a shelf in the back of the mall's bookstore. Who would find that fun?

I fall snugly into the narrow range between people who hate writing because they couldn't care less about it and people who hate writing because they have to do it. Writing is the getaway car for my brain, it takes me away from things I avoid doing, like working on my matlab code or cleaning the house or sending an email home.

So I like writing and have an easy time with it because I'm a hobbyist. That doesn't make me good at it. Often I don't have any point to make, and when I do, they don't get across. Readers, if I'm lucky enough to have any, would see something completely different from what I write, or what I think I write. This is normal - who knows exactly what Van Gogh was thinking when he painted Starry Night? I'm sorry, have I just put myself in the same league with Van Gogh? But hey, when it comes to doing art, in one aspect I have an advantage: I'm currently alive. If I write about donuts and you think I write about stars, I can tell you that no, those are donuts. Van Gogh can't tell you anything about his original intention. You just have to guess.

Which is fine, because art is supposed to do that to you. It wakes your imagination, your thoughts, your feelings, your everything. Once the piece of art is out there, it is you who choose how to take it. The artist, live or dead, has little to do with it now. Their work is no longer their baby. It is now a grown-up with full autonomy, and it gets to choose whether it wants to be stars or donuts. This is cool for you as readers but rather lame for the writer-artist. They made the piece, they are the poor parent who's stuck with this child now. The child could grow up to be a lovely person whom everyone loves, or they could be a total a**hole, or they could be so boring and characterless that no one would even notice if they disappear. The writer is the only one who has to work hard rearing their piece, hoping everyone would love it. Still, it doesn't always work.

------------------------------

This is temporarily the last piece in this series "A writing about writing". Thanks for staying until this point. I hope you find them pleasant.

Starry Bite by Ellen Brown @ELLE.ART

Which is fine, because art is supposed to do that to you. It wakes your imagination, your thoughts, your feelings, your everything. Once the piece of art is out there, it is you who choose how to take it. The artist, live or dead, has little to do with it now. Their work is no longer their baby. It is now a grown-up with full autonomy, and it gets to choose whether it wants to be stars or donuts. This is cool for you as readers but rather lame for the writer-artist. They made the piece, they are the poor parent who's stuck with this child now. The child could grow up to be a lovely person whom everyone loves, or they could be a total a**hole, or they could be so boring and characterless that no one would even notice if they disappear. The writer is the only one who has to work hard rearing their piece, hoping everyone would love it. Still, it doesn't always work.

------------------------------

This is temporarily the last piece in this series "A writing about writing". Thanks for staying until this point. I hope you find them pleasant.

Thứ Sáu, 4 tháng 12, 2015

A writing about writing - part 2

I'm not a story teller. That is why I don't think about writing books.

To tell a story, you have to have a story in mind. You have to imagine all the characters: what they do first thing when they get up, what they say to the barista at that local coffee shop where they are a regular, what they wear on a cold Tuesday... All these tiny things that you probably don't even notice when you read a story are what make the characters who they are. They make them imaginable for you as readers. They become alive in the story.

And you have to build the scenes, or the situations where your characters act in. You can put them in a poor house nested in a crappy neighborhood then give them cancer so their life becomes impossibly difficult and they will find the love of their life then but their life has become so impossibly difficult that it makes them cry and the love of their life cry and the readers cry. And then you decide to not kill them with cancer, you kill the love of their life instead. (A good thing about being a writer is that you can kill anyone in your book without getting arrested.)

Once you have the scenes set up, you have to put them together so they make a story. This is important because you shouldn't combine Korean dramas with John Green and a hint of Mark Haddon and call it your story. You can, but I won't read your book.

Putting your scenes together is what they call "organization" or "structure". Do you remember what they told you about how to write an essay? First your write down a thesis sentence - that is the theme of your essay. Then you write down sub-thesis sentences - each of them is the theme of one paragraph. Then you write down supporting ideas and details. Then you put in transitions to make the whole thing cohesive. Then you add introduction and conclusion and a title. Then, you have your essay. It is organized, smooth, well-supported, easy to follow, and will get an A from your teacher.

I'm not good at this. Writing to me is just catching thoughts and turning them into text. I don't make outline. Thoughts come and if they have a nice ring to them, I pick them, not in any particular order. It's like writing poetry. You write down a thought, then you write down a second thought. But the second thought has to rhyme with the first thought in some way, so you only have a few choices of how you can write it down. It's like putting a jigsaw puzzle together. There is only a few pieces that might fit with the one you have out, and there is only one piece that fits best. You try them out and choose the best one. Watch this:

My first thought: "I'm not writing poetry anymore"

My second thought: "Poems are sad"

"Poems" sound sadder than "Poetry", and repetitive patterns are sadder, too, (like when you are watching the rain), so I'm going to replace "poetry" with "poems" in my first thought. That way it sounds really sad.

"I'm not writing poems anymore

Poems are sad"

So now my third thought has to fit in the rhyme and the number of syllables and the stress patterns of the first two thoughts, and because there are not too many ways to fit in all of those things, I don't have a lot of choices to pick, which make it easier. It's like going to a shoe store and you only look at the shoes in your size because they will fit your feet. You don't have to look at the other shoes because they don't fit. If you just move to another country and you don't know your size there, you will have to try a lot of shoes on.

So my third thought could be "Roses are red" and cannot be "The chai latte I had yesterday at Panera tasted like soap" because "Roses are red" is shorter and "red" kind of rhymes with "sad", but "The chai latte I had yester at Panera tasted like soap" is too long and has nothing to rhyme with "sad" or "anymore".

But I won't put "Roses are red" in there because I don't like this thought. It is like finding shoes that fit but you won't buy them because you don't like them.

My writing is clear to me because it is my thoughts and I follow them. It is not clear to my readers because they don't know my thoughts. They don't know why I write about poetry after I write about structure of stories. These two thoughts stand next to each other in my head so I marry them to each other, but they look like strangers to my readers.

---------------------------------------------

Hi. Thank you for reading again. I'll write more later because this thing is getting very long and I'm trapped in Mark Haddon's style and I need to escape first.

Thứ Hai, 30 tháng 11, 2015

A writing about writing - part 1

I like writing. That is kind of a fact. When I was a little girl who thought she would become the greatest writer of all time, my parents had to either gently or violently hint at me that no, I wasn't so great, and even if I had a chance to become a great writer, it wouldn't be a very well-paid job. Writing is not a sexy career. Writers are these strangely dreamy and expectedly poor folks who often die at young ages if they are great at their job.

So I didn't become a writer. My parents and my potential readers probably feel quite relieved. I'm on a track to become a biologist, which is not anywhere close to writing, except that 200-page dissertation and a bunch of papers I have to write with the vocabulary that sounds like Greek because it was actually derived from Greek (and Latin - I respect a language that manages to create so much troubles for users so long after its death). And I spend most of my time avoiding writing them, which means I don't necessarily enjoy that kind of writing.

My parents were right, becoming a writer isn't easy. I read somewhere in an essay by Ann Patchett that she was annoyed when everyone just approached her and told her they had a story that she ought to write about, and that it would definitely be a great story, and the writing would just be final presentation, like putting cooked food from the stove top to the table. Except it isn't. Ann Patchett said in her essay that the story was just a very small part, the writing was the hardest part. The story is like a bag full of grocery, the writing is prepping and cooking and serving and cleaning and everything in between. And sometimes, the food isn't that good, or it isn't what your guests want for that dinner, or it is good for you but it is too salty for them, or they eat it too quickly to even appreciate it. (OK, this food analogy is mine, not Ann Patchett's, so don't quote her on that.)

I read a book written by an old friend. It was a fiction. It was okay. I mean, it wasn't one of those books that would make it into literature textbooks 100 years from now. It got out there, became popular for a little while, then probably disappeared. And that is how it goes for the majority of books. Really. Have you been to a bookstore lately? Or on Amazon? Or to the library? There are just so many books. I can't help but thinking there might be a chance that some books never even get read at all.

And that is why I admire my friend. She had a story, she put work into writing in down, she published it, she watched it getting welcomed and forgotten by readers. She faced the fact that her book might not even get read at all, after all those days and nights she put into writing it. She faced the fact that some people, or a lot of people, might read it and hate it. She faced the fact that some people might read it and would not understand it at all.

---------------------------------------------------------

This part doesn't belong to A writing about writing. I just think I drop you a note, because you happen to be among the 10% of my Facebook friends who don't mind reading long things hidden in a link. Thanks for reading. Leave a mark (a like, I guess, because that's pretty convenient), so I know you were here, and there is a bigger chance that I might keep writing. And if I choose to do so, I will write about how I write.

Đăng ký:

Bài đăng (Atom)